Choice Architecture - Energy Sector (last article in this series)

* This is the third and last in article triad focused on evidence-based Choice Architecture.

Whether by design or not, Choice Architecture surrounds us. Our behavior is affected by cues from the external environment that influence our behavior without necessarily depriving us from the capacity to make conscious choices. Warnings on cigarette packages, posted restaurant sanitary ratings, and the arrangement of items in a menu or supermarket shelves are few examples.

***

In my first article, I highlighted the view of Choice Architecture as a "Manipulation of Choice." Some argued that individuals may be irrational decision-makers, but they know more about their lives that the government decision-makers. Others cautioned that if the government designed Choice Architecture for the public, individuals won’t learn from their own mistakes. Intriguingly, the same argument has not been as loud of a concern about corporates and financial institutes using Choice Architecture to alter consumers purchasing behavior through different marketing strategies. This raises a question as to whether the public objections stem from a general negative attitude towards governmental agencies or a specific concern about the misuse of Choice Architecture. Whether the empirically testable, concrete benefits of Choice Architecture programs would win over the philosophical objections and concerns is for time to tell.

Here, I will focus on the Choice Architecture use in the field of Energy. The concept has been tested to examine whether it could help consumers make more energy-saving - hence, financial savings - decisions. I will share two field experiments that utilized Choice Architecture to decrease individual and industry consumption of electricity.

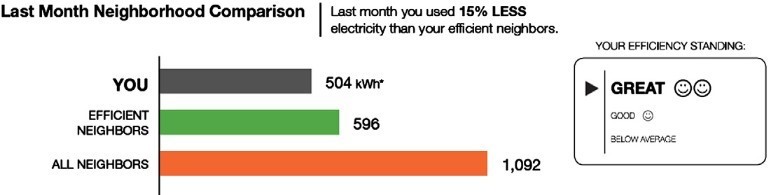

A classic filed experiment is the American electricity company Opower’s household mailers Home Energy Reports (HERs). It allows homeowners to compare their electricity usage to their neighbors'. The data suggest that this form of Choice Architecture was cheap to implement, easy to comprehend, did not intervene with people's choice to use more or less energy and led to decreased energy use. Opower used Choice Architecture in the form of Social Normative messages, a type of social influence that encourages social activity and outcomes as norm. The messages included a bar-graph comparison of a person’s electricity usage to their neighbors' to reduce electricity consumption. The use of Normative Messages with Injunctive Emoticons (i.e. emojis) effective at reducing consumption. Schultz et al. "The Constructive, Destructive and Reconstructive Power of Social Norms." Psychological Science. and 'Allcott and Kessler "The Welfare Effects of Nudges: A Case Study of Energy Use Social Comparisons." NBER working paper.

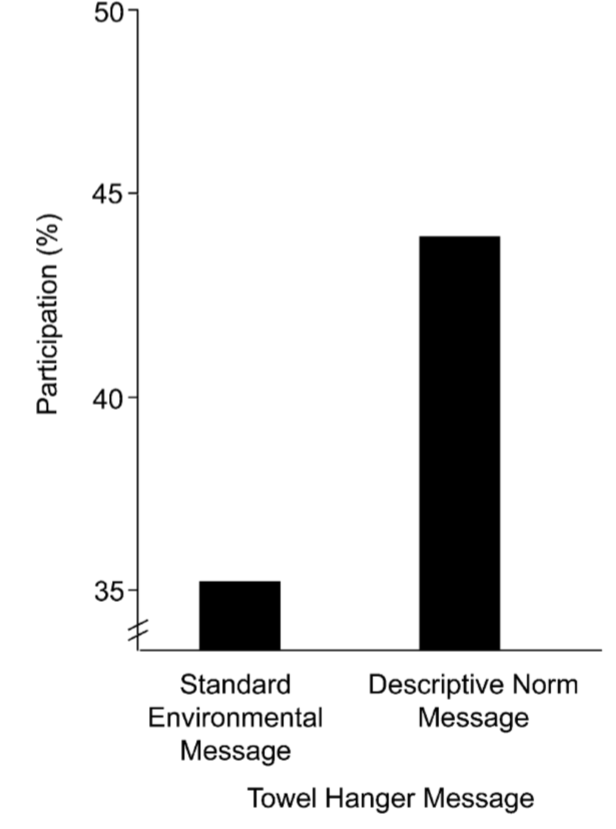

In another classic field experiment, Normative Messages was designed to promote towel re-use in hotel rooms to save energy. The control group received a printed message “Help save the environment .You can show your respect for nature and help save the environment by reusing your towels during your stay.” The treatment group received this message “Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment. Almost 75% of guests who are asked to participate in our new resource savings program do help by using their towels more than once. You can join your fellow guests in this program to help save the environment by reusing your towels during your stay.” The results suggest that normative sign yielded a towel reuse rate that was significantly higher than the industry standard sign. Goldstein, Cialdini and Griskevicius "A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels."J Consumer Res. * * *

* * *

The experiments covered in the article triad- and many others in the same vein - highlight the power of deploying evidence-based psychology and behavioral research to everyday life. I would, yet, be cautious here not to take all published results for face value; Not all data are created equally and "some data are more reproducible and trustable than others." Yet, few could argue against applying reproducible, high-quality science-based Choice Architecture tools to help us make better choices in a time where the majority of us could have a "clinical diagnosis" of FOBO - Fear of Better Options - stemming from pseudoscience beliefs and hunches that govern our choices.